It's the end of the month yet again, and time to post the reading roundup. It's been a weird month, considering I was gone right through the heart of it. Then of course, having to adjust back to east coast time was a killer. Yesterday it was our turn to host our neighborhood Memorial Day barbeque (meaning a 2-day cookfest prior to) and my sister came to visit. Now it's quiet again and I have time to get back to posting. So let's begin:

This month I focused on reading down the TBR pile, and it was a good month. Although I haven't been able to post (my reviews will be coming shortly now that I have some breathing space again) as often as I would like to, that doesn't mean that I didn't get a chance to read. Here's the lineup:

Translated Fiction:

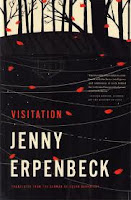

Visitation, by Jenny Erpenbeck

Kamchatka, by Marcelo Figueras

The Darkroom of Damocles, by Willem Frederik Hermans

Train to Budapest, by Dacia Maraini

The Informers, by Juan Gabriel Vasquez

General Fiction:

Matterhorn, by Karl Marlantes

Scandinavian Crime Fiction:

Red April, by Santiago Roncagliolo

The Snowman, by Jo Nesbo

The Leopard, by Jo Nesbo

Italian Crime Fiction:

The Whisperer, by Donato Carissi

The Terra-Cotta Dog, by Andrea Camilleri

The Snack Thief, by Andrea Camilleri

Spanish Crime Fiction:

Death on a Galician Shore, by Domingo Villar

I think that covers it, for a total of 13 books; not too bad.

other book related stuff:

1) My book group this month read The Long Song, by Andrea Levy-- which we all agreed that we liked.

2) Added to the Amazon Wishlist this month

That Awful Mess on the Via Merulana, by Carlo Emilio Gadda

Dancing Lessons for the Advanced in Age, by Bohumil Hrabal

3) Books bought this month

Anatomy of a Disappearance, by Hisham Matar

River of Shadows, by Valerio Valesi

4) I left the ARCs I intended to take on the cruise at home, so it's go time for them starting today.

I hate that my month was so chopped I couldn't get online much, but I'll remedy that starting tomorrow. So that's it -- happy reading to all!

Tuesday, May 31, 2011

Friday, May 27, 2011

Matterhorn, by Karl Marlantes

9780802119285

Atlantic Monthly Press/Grove Atlantic

March, 2010

592 pp.

Matterhorn is a novel set in 1969, only a few years before the end of American military involvement in Vietnam. The book focuses on a group of Marines -- Bravo Company -- who fought in that war, but the action centers around Waino Mellas, a young Ivy Leaguer reservist who finds himself deployed with Bravo Company out in the bush. Mellas' story is a journey unto itself -- he is completely green when the novel begins, but as the missions of Bravo Company progress, he becomes transformed -- not so much by war itself, but by the people with whom he lives, eats, and comes to depend on for survival. And while the novel is fictional, what happens is based largely on many of the author's own experiences, or those of others he knew in Vietnam. In that sense, Marlantes adds his point of view to those of others who've written about Vietnam, such as Philip Caputo, Tim O'Brien, John Del Vecchio, and a host of others. However, unlike his predecessors, Marlantes had to wait several years to get his story out. His original novel was some 1600+ pages, but over the years after several rejections and continually whittling down the size of the book, his publisher finally gave him his opportunity.

For this book, his first, the author won the Colby Award, which "recognizes a debut work of fiction or nonfiction that raises the public’s awareness of intelligence operations, military history, or international affairs." Matterhorn is a multi-faceted novel, but largely it is a novel based on conflict. Obviously, the Vietnam War itself fits that bill, but there are other forms of conflict at work as well on a human level. For example, in the ranks of Bravo Company there is contention between some of the enlisted men and their commanders, there are racial issues, there is a demarcation between new Marines and the more seasoned vets, and there are even collisions between those who make the Marines their career and those who are there for the short term. It's also a story of ambitions, especially among the colonels running the show, who care mostly about body counts and how the latest numbers are going to serve them well in their respective careers. Then there are the officers directly beneath them who spend part of their time thinking about the moves they should make to get in good with the upper echelon. For the war literature buff, there are also many horrific battle scenes along with the inherent blood, guts and gore and an almost Band of Brothers-type feel at times. But overall, it's a story about all of the people involved in carrying out the day-to-day operations of battle.

The Matterhorn of the title is a mountain in the thick of the jungle, near the border of Vietnam and Laos, which Bravo Company is ordered to take and hold. They are then ordered to abandon it, then comes a reversal and the Marines are ordered to retake it, -- this last order coming while Matterhorn is controlled by a group of NVA forces who have plenty of time to keep the exhausted Marines pinned down under heavy fire. This novel is the story of those missions, along with a look at the men who are out there on the ground, not knowing if each minute could be their last. Each phase of these actions has heartbreaking consequences, as friends lose friends, or as the soldiers of Bravo Company find themselves cut off from being resupplied or without air support in bad weather. The novel traces how this slice of the war plays out, from HQ on down the chain of command to the officers who lead Bravo Company, and from them down to the regular field grunts who carry out the orders on the ground. Marlantes graphically depicts the physical terrors of war in the Quang Tri jungle, including leeches, tigers, stinging ants, "immersion foot," being bombarded with Agent Orange (a nuisance of the job) and other horrific details. He also doesn't hold back on describing the horrors inherent in any war: death, injury, and loss of friends and companions. The hill becomes a symbol of the utter futility of this war as human limits are pushed to extremes in an effort to survive. The men of Bravo Company, many of them in their late teens, must not only push past the ordeals of the jungle, but they also find themselves in the midst of some very human obstacles. For example, some of the black Marines are questioning the America to which they will return, showing sympathy with the Black Panthers and trying to recruit other black soldiers to their cause. Race issues rear their ugly head several times throughout the novel, once in particular with devastating consequences. Yet via his characters, Marlantes makes the point that even within the black soldiers there are conflicts -- that while some preach black power and react against the all-too-real prejudice of whites, there are other black Marines who don't want to support their tactics. Marlantes also pulls back the curtain on how war is played out through the chain of command, often detailing the upper echelon's misunderstanding of what's really taking place out in the jungle. In one instance, Marines on the ground are left hanging -- without food, water or ammo -- because of some of the decisions made by superiors back at their headquarters, whose understanding of the conditions in the bush is practically nil. They give the men impossible deadlines on fulfilling various parts of their missions, often based solely on how much ground they feel could be covered in a given amount of time, judged solely from their interpretations of a map. While Mellas is angered enough at one point to try to kill one of his COs, thinking that his dead comrades are nothing more to his superior than pawns in a game of ambition and politics, the author also makes the point that the higher-ups are also under a great deal of pressure -- and that in the end, everyone is involved in a situation over which they ultimately have zero control.

There's very little sentimentality to be found in Matterhorn -- it is a gritty story about the realities and ugliness of war. The book is especially good at detailing the human toll of conflict, and I don't mean just the number of deaths or injuries sustained in this war. It is so well written that I literally could not put this book down until I had finished it, and that's no easy feat, considering it's well over 500 pages. I'm not a huge fan of war novels, especially the kind where the author gets into the nitty gritty of specific battle details, but this novel is different. The characters are real, portrayed without the author having to resort to stereotyping, and the key questions of this book are ones which I've been contemplating for some time. Why did we really get involved in Vietnam when it wasn't our war to fight? Was it worth losing so many lives?

I very highly recommend this book. There are some negative reviews floating around, but use your own judgment. This isn't a book for everyone, and not everyone will read it in the same way -- it will mean different things to different people. Don't let the thickness of this novel deter you. It reads very quickly and you will find yourself sucked in from the first page.

Atlantic Monthly Press/Grove Atlantic

March, 2010

592 pp.

You've got to understand what we do here...We fix weapons...Right now you're a broken guidance system for forty rifles, three machine guns, a bunch of mortars, several artillery batteries, three calibers of naval guns, and four kinds of attack aircraft. Our job is to get you fixed and back in action as fast as we can.

Matterhorn is a novel set in 1969, only a few years before the end of American military involvement in Vietnam. The book focuses on a group of Marines -- Bravo Company -- who fought in that war, but the action centers around Waino Mellas, a young Ivy Leaguer reservist who finds himself deployed with Bravo Company out in the bush. Mellas' story is a journey unto itself -- he is completely green when the novel begins, but as the missions of Bravo Company progress, he becomes transformed -- not so much by war itself, but by the people with whom he lives, eats, and comes to depend on for survival. And while the novel is fictional, what happens is based largely on many of the author's own experiences, or those of others he knew in Vietnam. In that sense, Marlantes adds his point of view to those of others who've written about Vietnam, such as Philip Caputo, Tim O'Brien, John Del Vecchio, and a host of others. However, unlike his predecessors, Marlantes had to wait several years to get his story out. His original novel was some 1600+ pages, but over the years after several rejections and continually whittling down the size of the book, his publisher finally gave him his opportunity.

For this book, his first, the author won the Colby Award, which "recognizes a debut work of fiction or nonfiction that raises the public’s awareness of intelligence operations, military history, or international affairs." Matterhorn is a multi-faceted novel, but largely it is a novel based on conflict. Obviously, the Vietnam War itself fits that bill, but there are other forms of conflict at work as well on a human level. For example, in the ranks of Bravo Company there is contention between some of the enlisted men and their commanders, there are racial issues, there is a demarcation between new Marines and the more seasoned vets, and there are even collisions between those who make the Marines their career and those who are there for the short term. It's also a story of ambitions, especially among the colonels running the show, who care mostly about body counts and how the latest numbers are going to serve them well in their respective careers. Then there are the officers directly beneath them who spend part of their time thinking about the moves they should make to get in good with the upper echelon. For the war literature buff, there are also many horrific battle scenes along with the inherent blood, guts and gore and an almost Band of Brothers-type feel at times. But overall, it's a story about all of the people involved in carrying out the day-to-day operations of battle.

The Matterhorn of the title is a mountain in the thick of the jungle, near the border of Vietnam and Laos, which Bravo Company is ordered to take and hold. They are then ordered to abandon it, then comes a reversal and the Marines are ordered to retake it, -- this last order coming while Matterhorn is controlled by a group of NVA forces who have plenty of time to keep the exhausted Marines pinned down under heavy fire. This novel is the story of those missions, along with a look at the men who are out there on the ground, not knowing if each minute could be their last. Each phase of these actions has heartbreaking consequences, as friends lose friends, or as the soldiers of Bravo Company find themselves cut off from being resupplied or without air support in bad weather. The novel traces how this slice of the war plays out, from HQ on down the chain of command to the officers who lead Bravo Company, and from them down to the regular field grunts who carry out the orders on the ground. Marlantes graphically depicts the physical terrors of war in the Quang Tri jungle, including leeches, tigers, stinging ants, "immersion foot," being bombarded with Agent Orange (a nuisance of the job) and other horrific details. He also doesn't hold back on describing the horrors inherent in any war: death, injury, and loss of friends and companions. The hill becomes a symbol of the utter futility of this war as human limits are pushed to extremes in an effort to survive. The men of Bravo Company, many of them in their late teens, must not only push past the ordeals of the jungle, but they also find themselves in the midst of some very human obstacles. For example, some of the black Marines are questioning the America to which they will return, showing sympathy with the Black Panthers and trying to recruit other black soldiers to their cause. Race issues rear their ugly head several times throughout the novel, once in particular with devastating consequences. Yet via his characters, Marlantes makes the point that even within the black soldiers there are conflicts -- that while some preach black power and react against the all-too-real prejudice of whites, there are other black Marines who don't want to support their tactics. Marlantes also pulls back the curtain on how war is played out through the chain of command, often detailing the upper echelon's misunderstanding of what's really taking place out in the jungle. In one instance, Marines on the ground are left hanging -- without food, water or ammo -- because of some of the decisions made by superiors back at their headquarters, whose understanding of the conditions in the bush is practically nil. They give the men impossible deadlines on fulfilling various parts of their missions, often based solely on how much ground they feel could be covered in a given amount of time, judged solely from their interpretations of a map. While Mellas is angered enough at one point to try to kill one of his COs, thinking that his dead comrades are nothing more to his superior than pawns in a game of ambition and politics, the author also makes the point that the higher-ups are also under a great deal of pressure -- and that in the end, everyone is involved in a situation over which they ultimately have zero control.

There's very little sentimentality to be found in Matterhorn -- it is a gritty story about the realities and ugliness of war. The book is especially good at detailing the human toll of conflict, and I don't mean just the number of deaths or injuries sustained in this war. It is so well written that I literally could not put this book down until I had finished it, and that's no easy feat, considering it's well over 500 pages. I'm not a huge fan of war novels, especially the kind where the author gets into the nitty gritty of specific battle details, but this novel is different. The characters are real, portrayed without the author having to resort to stereotyping, and the key questions of this book are ones which I've been contemplating for some time. Why did we really get involved in Vietnam when it wasn't our war to fight? Was it worth losing so many lives?

I very highly recommend this book. There are some negative reviews floating around, but use your own judgment. This isn't a book for everyone, and not everyone will read it in the same way -- it will mean different things to different people. Don't let the thickness of this novel deter you. It reads very quickly and you will find yourself sucked in from the first page.

Labels:

book reviews -- fiction

home and awake again!

Traveling to the west coast is great, except the part where I come home and can't sleep until 2 in the morning because I'm still on west coast time. It's generally about one and a half weeks until I get back in sync, and I try hard but fail to not nap during the day. I've slept through much of the last three days, getting nothing done. Oh well.

Anyway, I'm back and I have tons of books to post about, considering that I just spent 2 weeks on vacation and had lots of reading time. It will take a while to get them all down, but I'll get there. So please bear with me.

Anyway, I'm back and I have tons of books to post about, considering that I just spent 2 weeks on vacation and had lots of reading time. It will take a while to get them all down, but I'll get there. So please bear with me.

Friday, May 13, 2011

greetings from California

I have been waiting for a while to get back on to Blogger (perhaps it's time to switch to wordpress?) to post that I'm on vacation, so I'll have to wait until I get home to FL to post my reviews. Every year, Larry's company sends a few people on a cruise as a bonus -- this year we're off to Puerto Vallarta and Cabo San Lucas. Mazatlan was originally on the itinerary, but because of the upswing in violence there from all the drug cartels duking it out in 5-star hotel parking lots, the cruise line has decided it's probably not a good place for American tourists to be. Shame, really, because Larry and I have a favorite beach horseback ride place we love in Mazatlan, and now we have to skip that. Better safe than sorry, though.

Anyway, here's what I've read and what I'll be posting about, both here and over at the crime segments:

Kamchatka, by Marcelo Figueras (my new favorite novel of the year) -- a look at Argentina's Dirty War through the eyes of a child whose parents are politicos and on the run. I must say, this book is on my list of simply outstanding novels for this year -- and there's only one book on that list. That's how bloody good it is.

Train to Budapest, by Dacia Maraini -- a story in which a woman in the late 1950s goes looking for a Jewish childhood friend whose last known address was a concentration camp. On her way to find more information, she discovers others with their own stories to tell, and runs smack into the Hungarian uprising against the Soviets.

The Darkroom of Damocles, by Willem Frederik Hermans -- an amazing story about a man caught up in occupied Holland during WWII -- an existential novel about a guy who takes orders from another man no one has ever seen, landing him in trouble after the war is over. More later, but really really good.

for the crime segments:

The Whisperer, by Donato Carrisi -- on the blurb it says it's a "literary thriller," but it's actually neither. My advice -- a very mainstream kind of read, which is just sad; not up to my usual choices in translated crime fiction.

I'm currently one-quarter way through Jo Nesbo's newest, The Leopard, which I bought from the UK after The Snowman, because I couldn't wait another two years for it to be published in the US! I'm liking this one much better than The Snowman so far, but I'll definitely be back for the review.

a couple of notes: to Jackie, at Farm Lane Books -- Thanks for the review of King of the Badgers -- it's waiting for me when I get home. I'll read it straightaway!

to Col -- you're welcome, and there's so many relief efforts in the south where the tornadoes hit, but thanks for your offer of help. I must say, there is so much goodness in this world if people know where to look!

for everyone else, I'll be home the 23rd, back on line the 24th of May, and I'm spending most of the week on my balcony lounge chair reading, so I'll have a lot to talk about.

See you later, and I will be able to get email for a bit, but things will be quiet here until I get back.

Anyway, here's what I've read and what I'll be posting about, both here and over at the crime segments:

Kamchatka, by Marcelo Figueras (my new favorite novel of the year) -- a look at Argentina's Dirty War through the eyes of a child whose parents are politicos and on the run. I must say, this book is on my list of simply outstanding novels for this year -- and there's only one book on that list. That's how bloody good it is.

Train to Budapest, by Dacia Maraini -- a story in which a woman in the late 1950s goes looking for a Jewish childhood friend whose last known address was a concentration camp. On her way to find more information, she discovers others with their own stories to tell, and runs smack into the Hungarian uprising against the Soviets.

The Darkroom of Damocles, by Willem Frederik Hermans -- an amazing story about a man caught up in occupied Holland during WWII -- an existential novel about a guy who takes orders from another man no one has ever seen, landing him in trouble after the war is over. More later, but really really good.

for the crime segments:

The Whisperer, by Donato Carrisi -- on the blurb it says it's a "literary thriller," but it's actually neither. My advice -- a very mainstream kind of read, which is just sad; not up to my usual choices in translated crime fiction.

I'm currently one-quarter way through Jo Nesbo's newest, The Leopard, which I bought from the UK after The Snowman, because I couldn't wait another two years for it to be published in the US! I'm liking this one much better than The Snowman so far, but I'll definitely be back for the review.

a couple of notes: to Jackie, at Farm Lane Books -- Thanks for the review of King of the Badgers -- it's waiting for me when I get home. I'll read it straightaway!

to Col -- you're welcome, and there's so many relief efforts in the south where the tornadoes hit, but thanks for your offer of help. I must say, there is so much goodness in this world if people know where to look!

for everyone else, I'll be home the 23rd, back on line the 24th of May, and I'm spending most of the week on my balcony lounge chair reading, so I'll have a lot to talk about.

See you later, and I will be able to get email for a bit, but things will be quiet here until I get back.

Thursday, May 5, 2011

the Visit from the Goon Squad lucky winner --

is Becky, in Australia from Page Turners! Random.org decided #4 would get the book today, and that was her number.

For everyone else, thanks so much for coming by and for playing. I love giving books away (and I'm in the middle of yet another round of book purge) so I'll give you a heads up on the next one.

Congratulations to Becky!

For everyone else, thanks so much for coming by and for playing. I love giving books away (and I'm in the middle of yet another round of book purge) so I'll give you a heads up on the next one.

Congratulations to Becky!

Monday, May 2, 2011

Visitation, by Jenny Erpenbeck

9780811218351

New Directions Publishing

2010

Originally published as Heimsuchung, 2008

translated by Susan Bernofsky

Opening with the above epigraphs, Visitation is a rather stunning, although very short, novel of historical fiction that offers the stories of the inhabitants of a lakefront summer house in the woods of Brandenburg through the movement of time and history in Germany. The prologue opens twenty-four thousand years ago with an advancing glacier, then progresses geologically over the years until the Brandenburg lakes began to form. As the land comes to be settled, it too follows a natural progression -- it is parceled off and sold, a beautiful home is built, land is added, subtracted, reparceled, etc. The slow and natural progression of the landscape stands in stark contrast to the rapid events that play out throughout Germany and all of its accompanying turmoil as decades pass, but at the same time, what ultimately happens to this land and to the house mirrors what happens in this country during the twentieth century.

It is on one of these lakes that a wealthy farmer owns a large tract of land, and his daughters are each slated to receive their own parcels as their respective inheritances. But the farmer sells off parts of the land designated for his daughter Klara in three parts, to a coffee and tea importer, a Jewish manufacturer of fine cloth and an architect from Berlin, who is the builder of a fine house of “quality German workmanship.” The rise of the Nazis and the second world war result in changes of occupancy and ownership once again, and the home is requisitioned by the Russian Army as the soldiers come into Germany to liberate the country. As the powers that be begin to contemplate and to build the Berlin wall, the land and the home begin another round of inhabitants under the collectivization policies of the government of the GDR (East Germany). The fall of the wall and its aftermath also bring about their own changes. Through the entire story, the house and the land undergo a series of transformations, and the only thing that remains constant is the character of "The Gardener," a somewhat mysterious and symbolic figure whose story of the work he does on the land is related after each chapter. The author offers brief but very powerful glimpses into the stories of the residents as they move in and lay down a foundation of memories and histories. Happy times spent there also serve as a safe haven and an anchor for some characters in times far removed from their carefree days on the lake. Through it all people live out their private lives in the house and on its grounds, often in contrast to the very public upheavals that have occurred in a century of Germany's history.

This novel is highly reminiscent of Simon Mawer's excellent novel The Glass Room, where the author brought the events of twentieth-century European history to a particular house. But Visitation is vastly different -- where Mawer's book set forth the events of history chronologically in a traditional narrative style, Visitation isn't what most readers would consider a "conventional" novel. It's based more on differing personal perspectives rather than a straightforward chronicle of events. Within each chapter, people and events often float back and forth in time with no warning, and it can be a little disconcerting until you feel like you have more of a bigger picture. Erpenbeck writes her chapters in long paragraphs, so that a single event and connected thoughts are covered, generally relating back to the opening of the chapter so that events can shift or things can get a bit tangential before the chapter circles back and is over. There are times when the prose seems to transform from narrative to melody, as the author often repeats certain lines like refrains from a poem or song. And just as the style becomes comfortable, the author gives the reader a jolt. There are a couple of times where this happens -- first in a heartbreaking chapter from the perspective of a little girl in the Warsaw Ghetto (the only chapter that takes place away from the house), and second in a most disturbing chapter from the point of view of a Russian army officer. There are a few parts of the book that may seem tedious -- pieces of folklore, official documents, minor details about the house and grounds etc., but these things genuinely fit into and enhance the story and should not be glossed over. The characters have their own personas and voices, each with his or her own story, thoughts and feelings, all most excellently captured by the translator, and you cannot help but get caught up in these lives.

It's a beautiful book, and all of the things that make it less than conventional -- plus Erpenbeck's focus on the landscape (if even briefly) "coming to resemble itself once more" despite all of the tumult in our private lives and the world in which we live -- are what appealed to me as a reader. It's a challenging book, but if your focus is on the bigger picture rather than a chapter here and there, it's ultimately a rewarding reading experience.

New Directions Publishing

2010

Originally published as Heimsuchung, 2008

translated by Susan Bernofsky

"As the day is long and the world is old, many people can stand in the same place, one after the other." -- Georg Büchner

"If I came to you,

O woods of my youth, could you

Promise me peace once again?" -- Friedrich Holderlin

"When the house is finished, Death enters." -- Arabic proverb

"If I came to you,

O woods of my youth, could you

Promise me peace once again?" -- Friedrich Holderlin

"When the house is finished, Death enters." -- Arabic proverb

Opening with the above epigraphs, Visitation is a rather stunning, although very short, novel of historical fiction that offers the stories of the inhabitants of a lakefront summer house in the woods of Brandenburg through the movement of time and history in Germany. The prologue opens twenty-four thousand years ago with an advancing glacier, then progresses geologically over the years until the Brandenburg lakes began to form. As the land comes to be settled, it too follows a natural progression -- it is parceled off and sold, a beautiful home is built, land is added, subtracted, reparceled, etc. The slow and natural progression of the landscape stands in stark contrast to the rapid events that play out throughout Germany and all of its accompanying turmoil as decades pass, but at the same time, what ultimately happens to this land and to the house mirrors what happens in this country during the twentieth century.

It is on one of these lakes that a wealthy farmer owns a large tract of land, and his daughters are each slated to receive their own parcels as their respective inheritances. But the farmer sells off parts of the land designated for his daughter Klara in three parts, to a coffee and tea importer, a Jewish manufacturer of fine cloth and an architect from Berlin, who is the builder of a fine house of “quality German workmanship.” The rise of the Nazis and the second world war result in changes of occupancy and ownership once again, and the home is requisitioned by the Russian Army as the soldiers come into Germany to liberate the country. As the powers that be begin to contemplate and to build the Berlin wall, the land and the home begin another round of inhabitants under the collectivization policies of the government of the GDR (East Germany). The fall of the wall and its aftermath also bring about their own changes. Through the entire story, the house and the land undergo a series of transformations, and the only thing that remains constant is the character of "The Gardener," a somewhat mysterious and symbolic figure whose story of the work he does on the land is related after each chapter. The author offers brief but very powerful glimpses into the stories of the residents as they move in and lay down a foundation of memories and histories. Happy times spent there also serve as a safe haven and an anchor for some characters in times far removed from their carefree days on the lake. Through it all people live out their private lives in the house and on its grounds, often in contrast to the very public upheavals that have occurred in a century of Germany's history.

This novel is highly reminiscent of Simon Mawer's excellent novel The Glass Room, where the author brought the events of twentieth-century European history to a particular house. But Visitation is vastly different -- where Mawer's book set forth the events of history chronologically in a traditional narrative style, Visitation isn't what most readers would consider a "conventional" novel. It's based more on differing personal perspectives rather than a straightforward chronicle of events. Within each chapter, people and events often float back and forth in time with no warning, and it can be a little disconcerting until you feel like you have more of a bigger picture. Erpenbeck writes her chapters in long paragraphs, so that a single event and connected thoughts are covered, generally relating back to the opening of the chapter so that events can shift or things can get a bit tangential before the chapter circles back and is over. There are times when the prose seems to transform from narrative to melody, as the author often repeats certain lines like refrains from a poem or song. And just as the style becomes comfortable, the author gives the reader a jolt. There are a couple of times where this happens -- first in a heartbreaking chapter from the perspective of a little girl in the Warsaw Ghetto (the only chapter that takes place away from the house), and second in a most disturbing chapter from the point of view of a Russian army officer. There are a few parts of the book that may seem tedious -- pieces of folklore, official documents, minor details about the house and grounds etc., but these things genuinely fit into and enhance the story and should not be glossed over. The characters have their own personas and voices, each with his or her own story, thoughts and feelings, all most excellently captured by the translator, and you cannot help but get caught up in these lives.

It's a beautiful book, and all of the things that make it less than conventional -- plus Erpenbeck's focus on the landscape (if even briefly) "coming to resemble itself once more" despite all of the tumult in our private lives and the world in which we live -- are what appealed to me as a reader. It's a challenging book, but if your focus is on the bigger picture rather than a chapter here and there, it's ultimately a rewarding reading experience.

fiction from Germany

May -- attacking the tbr pile

This is not my tbr pile, but it could be. So this month I'm focusing on books I've bought but haven't yet read. They're everywhere, they go back years, so it's going to be a real mixed bag of stuff this month.

Possible contenders include

The Journey of Anders Sparrman, by Per Wästberg

We the Drowned, by Carsten Jensen

The Three Christs of Ypsilanti, by Milton Rokeach

I Curse the River of Time, by Per Petterson

Museum of the Weird, by Amelia Gray

To get back on track for the Chinese Literature challenge, I'll definitely be reading the 4-volume Journey to the West. And I have some awesome crime reads lined up, including Jo Nesbo's The Leopard, Camilla Lackberg's The Preacher, and Splinter, by Sebastian Fitzek.

It should be an interesting mix.

Possible contenders include

The Journey of Anders Sparrman, by Per Wästberg

We the Drowned, by Carsten Jensen

The Three Christs of Ypsilanti, by Milton Rokeach

I Curse the River of Time, by Per Petterson

Museum of the Weird, by Amelia Gray

To get back on track for the Chinese Literature challenge, I'll definitely be reading the 4-volume Journey to the West. And I have some awesome crime reads lined up, including Jo Nesbo's The Leopard, Camilla Lackberg's The Preacher, and Splinter, by Sebastian Fitzek.

It should be an interesting mix.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)