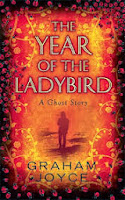

Gollancz/Orion, 2013

265 pp

hardcover (UK)

The Year of the Ladybird surprisingly has much the same feel as Stephen King's recent Joyland, both set in kitschy kind of amusement places that used to be everywhere but which now are found largely in memories. They're also both coming-of-age-stories, both have a slight infusion of the supernatural, and both capture a snapshot of a certain place at a certain time. Both main heroes start out young and naive; by the end of the story they've learned something not only about themselves, but about the way the world really works. Ghosts and fortunetellers play a role in both; King's excursion into the ethereal has much more to do with the plot of the story, while Joyce's foray into the phantasmal is much more limited to the psyche of the main character. To be really honest, while I enjoyed Mr. Joyce's writing here, the ghost story neither grabbed nor thrilled me; nor did it give me even the slightest outbreak of goosebumps. I'm also not a huge fan of coming-of-age stories either, but what's really well done here is the time-capsule element. He describes this small piece of yesteryear so nicely that it's almost like being there, and the wide variety of people around the main character really enliven what could have otherwise been a been there, read-that-dozens-of-times kind of book.

It's 1976. England is sweltering, the political right is in turmoil as fears of immigrant job takeovers loom large and people are starting to not only notice but to get angry. A heat wave has enveloped large parts of the country, water usage has been restricted, and and large clouds of lady bugs (ladybirds) are everywhere. In that milieu, David, a young college student, has decided that rather than take up his stepdad's offer of employment in his construction business, he'll be working at a holiday camp in the seaside town of Skegness. The story is told from his own first-person perspective, and as he notes, in 1976, the "heyday of the British holiday camps had slipped," because cheaper flights were allowing more people to take their vacations in exotic locations. David had gone there largely out of curiosity: earlier in his childhood, he'd found a photo showing his real father and himself at age three with the word "Skegness" written on the back. He doesn't remember it, of course, and his mom and stepdad are unhappy with his choice to work there, but he takes the job anyway. He works as a "Greencoat," someone who does pretty much anything, helping with the entertainments for all ages -- calling bingo, supervising sand-castle building among the younger kids, doing show lighting etc., etc. While he's there, he meets all manner of people who also work in the holiday camp, falls for the wrong woman before finding the right one, is introduced to an ultra right-wing group called "The Way Forward," and learns how things really work in the world. David is bothered throughout the story with a sense of dread as if something terrible's about to happen, and he also encounters two strange figures along the seaside whom no one else but he can see.

|

| Butlin's Skegness Holiday Camp, from bygonebutlins.com |

If you've read Water for Elephants, you're familiar with how well the author described day-to-day life and the behind-the-scenes rivalries and relationships in the the depression-era circus; Mr. Joyce does the same here for the holiday camp. There's a great variety of characters that he brings to life so nicely: the tough-guy abusive husband who pays David to look after his wife and report back to him, the magician, the Italian singer, the fortuneteller, David's constantly intoxicated roommate, the dancer, as well as the people in charge and who work behind the scenes. The tourists, of course, are a large part of the story, as well as the daily activities -- sandcastle building, dance contests, donkey rides for the overweight women, beauty contests, bingo -- all of which are rewarded with gala ceremonies and rock candy. I'm not sure if there's an equivalent here in America since in summer it's mainly kids who go to camp, but it doesn't matter -- the camp is described so well that a clear picture will form in your mind as you read. And all through the novel runs the metaphor of the ladybirds in flight.

As I noted, the ghost story isn't frightening, and I think it's just here to illustrate a point and aid in David's arrival at self awareness. Considering that I read this book hoping for even a mild frisson of fright, I was a bit disappointed; considering the entire book is about the progression of the main character as he comes into his own awareness of the world around him, the ghost story definitely plays second fiddle here. What kept me reading were the holiday camp scenes, the descriptions of growing political unrest and turmoil of the time, and the people in this book. The ending may seem a little ambiguous, but as I always say, if authors always wrap things up nice and tidy without leaving any questions behind, what's to think about?

If you're looking for an eerie, unearthly sort of read, this isn't the one. If you're into the bildungsroman genre, then this one may interest you as well. Even better, if the appeal lies in picking up a book with a wide range of characters, or getting sucked into novel where the author paints a portrait of a particular place at a particular time, then definitely add this one to your tbr pile.

No comments:

Post a Comment

I don't care what you say about what I write, but do be nice. Thanks!